United Nations members should make a concerted international effort to initiate judicial investigations into grave human rights violations in the Democratic Republic of Congo documented by the UN and bring those responsible to justice, Human Rights Watch said today.

On October 1, 2010, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights published the report of its human rights mapping exercise on Congo. The report covers the most serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law committed in Congo between March 1993 and June 2003.

"This detailed and thorough report is a powerful reminder of the scale of the crimes committed in Congo and of the shocking absence of justice," said Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch. "These events can no longer be swept under the carpet. If followed by strong regional and international action, this report could make a major contribution to ending the impunity that lies behind the cycle of atrocities in the Great Lakes region of Africa."

The report documents 617 violent incidents, covering all provinces, and describes the role of all the main Congolese and foreign parties responsible - including military or armed groups from Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, and Angola.

An earlier version of the report was leaked to the news media in August. The Rwandan government, whose troops are accused of some of the most serious crimes documented in the report, reacted angrily, threatening to pull its peacekeepers out of UN missions if the UN published the report.

"The UN has done the right thing by refusing to give in to these threats and by publishing the report," Roth said. "This information has been stifled for too long. The world has the right to know what happened, and the victims have a right to justice."

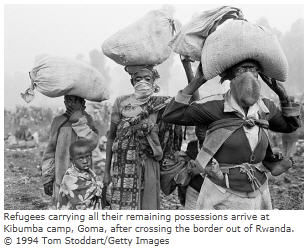

The UN had tried to investigate some of the events described in the report, notably in 1997 and 1998, but these investigations were repeatedly blocked by the Congolese government, then headed by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, father of the current president, Joseph Kabila. Despite those efforts, information about massacres, rapes, and other abuses against Rwandan refugees and Congolese citizens in the late 1990s was published at the time by the UN and by human rights organizations. However, no action was taken to hold those responsible to account.

"The time has come to identify and prosecute the people responsible for carrying out and ordering these atrocities, going right up the chain of command," Roth said. "Governments around the world remained silent when hundreds of thousands of unarmed civilians were being slaughtered in Congo. They have a responsibility now to ensure that justice is done."

One of the most controversial passages of the report concerns crimes committed by Rwandan troops. The UN report raises the question of whether some might be classified "crimes of genocide". The possible use of the term "genocide" to describe the conduct of the Rwandan army has dominated media coverage of the leaked report.

"Questions of qualification and terminology are important, but should not overshadow the need to act on the content of the report regardless of how the crimes are characterized," Roth said. "At the very least, Rwandan troops and their Congolese allies committed massive war crimes and crimes against humanity, and large numbers of civilians were killed with total impunity. That is what we must remember, and that is what demands concerted action for justice."

The report has received widespread support from Congolese civil society, with 220 Congolese organizations signing a statement welcoming the report and calling for a range of mechanisms to deliver justice.

The mapping exercise has its origins in the UN's earlier investigations into crimes committed in Congo from 1993 to 1997. In September 2005, the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo, MONUC, discovered three mass graves in Rutshuru, in North Kivu province of eastern Congo, relating to crimes committed in 1996 and 1997. The gruesome discovery acted as a trigger to re-open investigations. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, with the support of the UN Secretary-General, initiated the mapping exercise and broadened the mandate to include crimes committed during Congo's second war from 1998 to 2003.

The mapping exercise was conducted with the support of the Congolese government. However, the Congolese justice system has neither the capacity nor sufficient guarantees of independence to adequately ensure justice for these crimes, Human Rights Watch said. The report therefore suggests other options, involving a combination of Congolese, foreign, and international jurisdictions.

These could include a court with both Congolese and international personnel as well as prosecution by other states on the basis of universal jurisdiction. Human Rights Watch supports the establishment of a mixed chamber, with jurisdiction over past and current war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Congo.

Countries in the region whose armies are implicated in the report should carry out their own investigations and initiate action against individuals responsible for crimes, Human Rights Watch said.

The report is both important for highlighting past injustices and relevant to the situation in present-day Congo, Human Rights Watch said.

"This is more than a historical report," Roth said. "Many of the patterns of abuse against civilians documented by the UN team continue in Congo today, fed by a culture of impunity. Creating a justice mechanism to address past and present crimes will be crucial to ending this cycle of impunity and violence."

Related articles

- • DRC and Rwanda Sign Declaration of Principles for Peace in Eastern Congo (April 25, 2025)

- • European Union Sanctions Rwanda and M23 Officials over Congo Conflict (March 17, 2025)

- • Canada and Germany Impose Sanctions on Rwanda for Supporting M23 Rebels (March 4, 2025)

- • UK Suspends Financial Aid to Rwanda Over M23 Rebellion (February 25, 2025)

- • European Union Suspends Defence Consultations with Rwanda (February 24, 2025)

- • Tshisekedi Announces Government of National Unity and Calls for Unity Against M23 Rebels (February 23, 2025)

- • UN Security Council Calls on Rwanda to Stop Supporting M23 Rebels in DR Congo (February 22, 2025)

- • US Sanctions Rwanda's Minister James Kabarebe for Central Role in DR Congo Conflict (February 20, 2025)

- • Rwanda-Backed M23 Rebels Summarily Executed Children in Bukavu, UN Reports (February 19, 2025)

- • DR Congo Citizens Head to Polls to Elect President, Members of Parliament (December 20, 2023)

- • DR Congo Leopards win first edition of FIBA AfroCan championship (July 28, 2019)

- • 'Deadly environment' plus 'political and social' obstacles hinder Ebola fight, Security Council hears (July 24, 2019)

- • Ebola outbreak declared an international Public Health Emergency (July 17, 2019)

- • Felix Tshisekedi Sworn In as DR Congo President (January 24, 2019)

- • Constitutional Court Declares Tshisekedi Winner of Presidential Election (January 19, 2019)

- • Felix Tshisekedi Vows to Be the President of All Congolese (January 10, 2019)

- • Felix Tshisekedi Elected DR Congo President (January 10, 2019)

- • DR Congo Delays Results of December Election (January 6, 2019)

- • Botswana Urges Joseph Kabila to Step Down (February 26, 2018)

- • No elections in DR Congo in December without electronic voting machines: INEC (February 13, 2018)

- • US Warns DR Congo Against Electronic Voting for Delayed Election (February 12, 2018)

- • Felix Tshisekedi accuses INEC of illegally prolonging Kabila's mandate (October 24, 2017)

- • DRC Seeks Arrest of Presidential Candidate Moise Katumbi (May 19, 2016)

- • Papa Wemba Is Buried in Kinshasa (May 4, 2016)

- • Papa Wemba Awarded Highest National Honor as Thousands Pay Tribute (May 2, 2016)

- • Peacekeepers, Congo Army to Resume Joint Fight Against Rwandan Rebels (January 28, 2016)

- • Political tensions 'running high' in DR Congo ahead of 2016 elections (October 7, 2015)

- • UN Report Blames Ugandan Islamists for 237 Killings in DR Congo (May 14, 2015)

- • Rights Groups: DR Congo Must Free Pro-democracy Activists (April 13, 2015)

- • DRC Army Putting Pressure on FDLR (April 1, 2015)