McAlary report (Real) - Download 506k

An international human rights group says child soldiers as young as 13 are serving in the army of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Human Rights Watch is urging the Congolese government to release the estimated 300 to 500 youngsters, whom they inherited when they absorbed the armies of former rebel warlords under terms of a peace plan. The Congolese situation is not unique. The United Nations estimates that 300,000 children serve as indentured soldiers in rebel and government armies around the world. VOA's David McAlary reports from Washington that if the youngsters survive their ordeal, they are usually left with severe psychological wounds.

![]()

Listen to McAlary report (Real) ![]()

Human Rights Watch says the average child soldier is aged 13-17, but some have been as young as eight or nine. Most are unwilling militants, abducted from their villages to serve as soldiers, guerrilla fighters, or supporting roles in armed conflicts in more than 50 countries. They wield weapons in battle, serve as human mine detectors, participate in suicide missions, and act as spies, messengers, or lookouts.

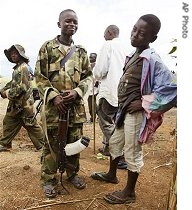

Child solders stand talking near the small village of Boga near Bunia, Democratic Republic of Congo (2004 file photo)

"Children by the thousands have been literally kidnapped from their homes and their communities, and subjected to the most horrific forms of violence," said the children's rights advocate for Human Rights Watch, Jo Becker.

She says children typically make obedient soldiers because they are vulnerable and easily intimidated.

"They are forced to commit atrocities against members of their own community, sometimes members of their own family," she said. "The girls are often used as wives by the commanders and subjected to what is essentially sexual slavery."

"They are terrorized into compliance by being threatened with death, if they try to run away, and even being forced to kill other children who try to escape," she added.

Studies show that these youths are left with severe psychological scars.

In Belgium, Ghent University researcher Ilse Derluyn and colleagues interviewed more than 300 former child soldiers who had been abducted by the northern Ugandan rebel movement, Lord's Resistance Army.

Ninety seven percent suffered post-traumatic stress disorder after an average of two years in servitude. Derluyn says their problems were typical of this syndrome -- persistent nightmares and trouble sleeping and concentrating that lingered long after their ordeal ended.

"These do not get better with time," said Derluyn. "Even the children who returned a long time ago from their abduction still suffer from post-traumatic stress reaction."

The researchers found that children suffered less stress if their parents were still alive, especially their mother. Derluyn says reuniting them with their families and previous social networks would help restore their psychological health. But many of the children are not so fortunate.

"A lot of children do not have parents anymore, or one of the parents has died," she said. "Also, they committed a lot of atrocities against their own neighborhoods sometimes, so it is quite difficult to reintegrate them into the neighborhood and the living situation."

The international community has focused on the child soldier problem in recent years. The 2002 Convention on the Rights of the Child, the International Labor Organization, and the African Charter on Rights and Welfare of the Child ban the use of children as soldiers. The International Criminal Court defines child military recruitment as a war crime.

The U.N. Security Council has condemned the practice and passed six resolutions against it since 1999. The most recent, in 2005, outlines a system of reporting and monitoring.

The United Nations Children's Fund has worked with governments and private organizations to demobilize and rehabilitate thousands of children in Sierra Leone, southern Sudan, Afghanistan and other countries.

But Jo Becker of Human Rights Watch says that the Security Council has applied sanctions only twice. Last year it imposed travel bans on and froze assets of recruiters in Democratic Republic of Congo and Ivory Coast. She says sanctions must be more common.

"What we need are concrete actions that show that the legal framework is not just words on paper," said Ms. Becker. "We do need active prosecution by national courts, as well as ad hoc tribunals and the International Criminal Court. Another thing we need is strong action by the U.N. Security Council that will impose targeted measures against the parties that are responsible."

Ms. Becker says individual nations should also impose their own sanctions against those who traffic in child soldiers.

Related articles

- • DR Congo Delays Results of December Election (January 6, 2019)

- • Security Council extends UN mission, intervention force in DR Congo for one year (March 28, 2014)

- • U.S. sending more personnel to Uganda to hunt LRA leader Joseph Kony (March 24, 2014)

- • Kabila Congratulates Congo Army for Defeating M23 Rebels (October 30, 2013)

- • Rwanda 'recruiting for M23 rebels' (July 31, 2013)

- • DR Congo Will Not Negotiate With M23 Rebels, Government Says (November 19, 2012)

- • M23 Rebels Committing War Crimes (September 11, 2012)

- • Kagame Is A Problem for The U.S. and The U.K. (June 23, 2012)

- • US blocking UN report on Ntaganda rebels, Human Rights Watch says (June 21, 2012)

- • Congo Government Says Bosco Ntaganda Rebels Trained in Rwanda (June 10, 2012)

- • Rwanda Should Stop Aiding War Crimes Suspect Bosco Ntaganda: Human Rights Watch (June 4, 2012)

- • Kony 2012 video director detained (March 16, 2012)

- • LRA rebel leader Joseph Kony target of viral campaign video (March 7, 2012)

- • UN, AU vow to eradicate Ugandan rebel group LRA in 2012 (January 5, 2012)

- • Obama Sends Troops to Help Fight the LRA (October 14, 2011)

- • Case of UN Employee Caught Smuggling Minerals Not Unique (August 25, 2011)

- • UN envoy tells Security Council of improving security, remaining threats (June 9, 2011)

- • Rights Groups: Strengthen Civilian Protection Before Elections (June 9, 2011)

- • Germany: Groundbreaking Trial for Congo War Crimes (May 2, 2011)

- • Military Operations Have Weakened the LRA, Says UN (February 23, 2011)

- • UN launches patrols to head off rebel violence during holiday season (December 1, 2010)

- • US President Barack Obama outlines plan to defeat Ugandan LRA rebels (November 25, 2010)

- • Four African nations crack down on LRA (October 16, 2010)

- • UN DR Congo Report Exposes Grave Crimes (October 1, 2010)

- • LRA: UNHCR relocates 1,500 refugees from CAR to the DRC (August 24, 2010)

- • Report: Uganda LRA rebels 'on massive forced recruitment drive' (August 12, 2010)

- • Huge DR Congo gold mine to open, displacing 15,000 (July 22, 2010)

- • Report Says Uganda's Elusive LRA Rebel Almost Caught Last Year (June 24, 2010)

- • Joint Government and UN Inquiry Needed into Death of Floribert Chebeya (June 3, 2010)

- • U.S. Official Sees Improvement in Africa's Great Lakes Region (May 26, 2010)