Third Congo Warlord to Face Justice

By IWPR | Published February 7, 2008

Detention of another militia leader from Ituri follows a sensitive period where Congo's government was enticing rebel groups to lay down arms and make peace.

By Lisa Clifford in The Hague (AR No. 155, 07-Feb-08)

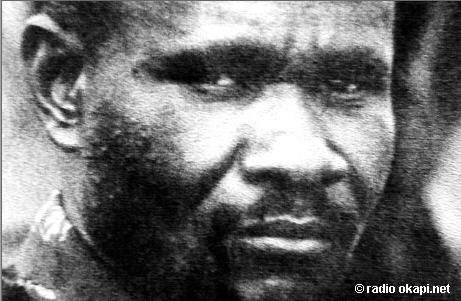

Human rights groups hope the arrest of a former rebel leader from the Ituri region of the Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC, will lead international prosecutors higher up the chain to other military and civilian leaders accusing of committing atrocities in local wars.Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui, the former leader of the militia group called the National Integrationist Front, FNI, was arrested by the DRC authorities in the capital Kinshasa on February 6 and transferred immediately to the custody of the International Criminal Court, ICC. He arrived at the war crimes court's headquarters the following day.

Ngudjolo joins two other ICC indictees in the court's Scheveningen detention unit. Like him, they are from Ituri and are accused of carrying out war crimes in a bloody ethnic conflict in this northeastern province. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, head of the Union of Congolese Patriots, UPC, was transferred in 2006 and Germain Katanga, a leader of the Patriotic Resistance Force, FRPI, in late 2007.

Just days ago it was a different story for Ngudjolo, a former nurse from Bunia whom ICC prosecutors accuse of six counts of war crimes and three of crimes against humanity in connection with an attack on a village in Ituri. He and two other top rebel leaders from Ituri were in the capital to undergo military training after agreeing to demobilise as paramilitaries and accept jobs as colonels in the regular army.

All three have been accused of war crimes, and the idea that they should simply be incorporated into the DRC military with apparent impunity was controversial both in the country and abroad.

Human rights activists applauded Ngudjolo's arrest, saying it sent an important signal to those in Congo who consider themselves untouchable.

"We have condemned this cycle of impunity in the DRC whereby warlords - instead of being prosecuted for the crimes they committed against civilians - are being promoted. It has been a common practice in Congo to reward war criminals with positions in the army," said Geraldine Mattioli from Human Rights Watch.

"It sends the wrong signal to warlords - that committing crimes is a good way to get to the top of the army."

ICC prosecutors allege that Ngudjolo - who is of Lendu ethnicity - planned and executed an attack on the Hema village of Bogoro in February 2003, during which which 200 civilians died. He is accused of responsibility for murders, inhumane acts, pillaging, sexual enslavement and using child soldiers.

Ngudjolo allegedly urged fighters under his command to "wipe out" Bogoro, which at the time was under the authority of the rival UPC, a mainly Hema group.

"Hundreds were killed, maimed or terrorised," said ICC deputy prosecutor Fatou Bensouda. "Women were forced to become sexual slaves. The village was pillaged by the FNI forces and razed to the ground. The civilian population of Bogoro had no choice but to get out."

Katanga is also charged in connection with the same attack, which prosecutors allege was carried out by a joint force of FRPI and FNI guerrillas.

Bensouda told IWPR it would be "very convenient" to try the two men together and said prosecutors were considering asking judges to join the cases.

Katanga was arrested in connection with an unrelated incident, and was brought to The Hague after several years in custody in Kinshasa.

Ngudjolo's journey to the Netherlands was rather different.

He was appointed a colonel in the Congolese army in December 2006, and arrived with much fanfare in Kinshasa in November 2007, along with fellow rebel leaders Peter Karim and Cobra Matata.

Karim was in charge of the FNI when a Nepalese peacekeeper died and seven others were taken hostage during fighting in May 2006. Matata took over command of the FRPI after Katanga's arrest, and human rights groups say the group continued to commit serious abuses, including the unlawful arrest and torture of local officials, some of whom were executed.

Eugène Bakama Bope, president of the Friends of the Law in Congo group, greeted the news of Ngudjolo's arrest with "joy", but said more detentions were needed. "For us, warlords like Peter Karim and Cobra Matata who still occupy positions of command within the Congolese military must also be prosecuted for their crimes."

The ICC issued the arrest warrant for Ngudjolo in July 2007, at a time when the DRC authorities were negotiating to reel him and the two other commanders to Kinshasa.

The warrant was sealed, and was only revealed on February 7 this year. Bensouda said this delay was designed to ensure "processes" were in place to ensure the smooth transfer of Ngudjolo to The Hague.

Mattioli, however, speculated that the court and the Congolese government waited because they did not want to derail the demobilisation process. "They wanted to get the arms and soldiers out of the bush," she said.

At that time, fighting between the army and another rebel group led by Laurent Nkunda was intensifying in the neighbouring North Kivu province. Analysts say an ICC arrest warrant against a rebel leader like Ngudjolo at that point could have scuppered any chance of negotiating peace with Nkunda.

After years of war, rival militias including Nkunda's signed a peace deal in North Kivu last month. They were promised an amnesty, though not for war crimes.

Bakama believes that Ngudjolo's arrest could now be causing Nkunda and others some concern, undermining their hopes that making peace would automatically confer impunity for past actions. "Warlords like Laurent Nkunda think that after the peace talks in Goma, all their actions will be granted amnesty," he said.

With Ngudjolo in ICC custody, human rights groups are concerned that Karim and Matata could head back into the bush. But that has not happened so far, and they not be in danger of imminent detention. Bensouda suggested the court was turning its attention from Ituri to look at cases of mass sexual violence, forced displacement and killings elsewhere in eastern Congo.

"We continue to monitor crimes committed in Ituri, but we are moving onto the next phase and are looking at other parts of the DRC, and right now we are looking to investigate in the Kivus," she said.

The court is also investigating officials from the DRC and other countries who financed and organised the various militias. "We're looking at who is supporting these people," said Bensouda.

That is welcome news for Human Rights Watch's Mattioli, who urged the court to reach higher and further.

"Without arms, without financial support, none of these rebel groups would have been able to do what they did in Ituri," she said.

Lisa Clifford is an international justice reporter in The Hague.

Related articles

- • UN Security Council Calls on Rwanda to Stop Supporting M23 Rebels in DR Congo (February 22, 2025)

- • 'Deadly environment' plus 'political and social' obstacles hinder Ebola fight, Security Council hears (July 24, 2019)

- • Ebola outbreak declared an international Public Health Emergency (July 17, 2019)

- • DR Congo Delays Results of December Election (January 6, 2019)

- • Moise Katumbi blocked from entering DR Congo (August 3, 2018)

- • At least 30 dead after massacres in Ituri (March 2, 2018)

- • ICC Confirms 14-Year Sentence Against Thomas Lubanga (December 1, 2014)

- • ICC sentences Germain Katanga to 12 years (May 23, 2014)

- • At least 60 killed as train derails in Katanga province (April 23, 2014)

- • ICC finds Germain Katanga guilty of war crimes and crime against humanity (March 7, 2014)

- • Bosco Ntaganda Attacked Civilians on Ethnic Grounds, ICC Prosecutor Says (February 10, 2014)

- • Rwanda 'recruiting for M23 rebels' (July 31, 2013)

- • DR Congo Asks Rwanda to Turn Over M23 Rebel Leaders (July 26, 2013)

- • Rebel Leader Bosco Ntaganda Makes First Appearence Before the ICC (March 26, 2013)

- • Bosco Ntaganda in the International Criminal Court's custody (March 22, 2013)

- • International Criminal Court Acquits Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui (December 18, 2012)

- • DR Congo Will Not Negotiate With M23 Rebels, Government Says (November 19, 2012)

- • M23 Rebels Committing War Crimes (September 11, 2012)

- • DR Congo, Rwanda Sign Pact to Fight Rebels in Eastern Congo (July 15, 2012)

- • Kagame Is A Problem for The U.S. and The U.K. (June 23, 2012)

- • US blocking UN report on Ntaganda rebels, Human Rights Watch says (June 21, 2012)

- • ICC Prosecutor Seeks 30 Years for Thomas Lubanga (June 13, 2012)

- • Congo Government Says Bosco Ntaganda Rebels Trained in Rwanda (June 10, 2012)

- • Rwanda Should Stop Aiding War Crimes Suspect Bosco Ntaganda: Human Rights Watch (June 4, 2012)

- • UN Report Accuses Rwanda of Supporting Bosco Ntaganda Rebels (May 28, 2012)

- • ICC Prosecutor Seeks New Charges Against Ntaganda, FDLR Leader (May 14, 2012)

- • Kabila's Position on The Arrest of Ntaganda 'Has Not Changed' (April 13, 2012)

- • Kabila, Army Chief of Staff head to eastern Congo to deal with defectors (April 10, 2012)

- • DR Congo Government Warns Bosco Ntaganda He May Face Justice (April 6, 2012)

- • Thomas Lubanga found guilty of using child soldiers (March 14, 2012)